Call the Beekeeper!

O’Neil immediately cordoned off the area round the tree to warn customers to keep their distance. As the long-time neighbor of a beekeeper, she confidently identified the melon-sized mass of insects as honeybees and knew that it was important to ensure their safe removal without the use of pesticides or chemicals.

After snapping a few photos to confirm the ID, O’Neil called the Lexington Bee Company, whose owner and head beekeeper Alix Bartsch is the Swarm Coordinator for the Middlesex County Beekeepers Association. Bartsch immediately sent out a swarm alert by text and email to her roster of local beekeepers who volunteer to capture honeybee swarms and re-house them in their own hives. As she explained in a phone call the next day, beekeepers’ participation is crucial, as “no reputable exterminator will exterminate honeybees, because they’re such beneficial insects.”

Within half an hour of O’Neil’s call, Wayland-based beekeeper Jane Sebring and her husband Richard Sebring arrived in full protective gear. They set up a tall step ladder, and over the next hour tried various tactics to lure the bees from their temporary resting place.

Masked, gauntleted and gloved, perched atop the step ladder, Richard Sebring first used a large soft bee brush to sweep the insects into an orange plastic box. When the gentle approach left a considerable cluster still in the tree, he sawed off first one, then a second branch, that Jane corralled with its full bee-load into a second box. (When not coaxing recalcitrant bees out of a tree or otherwise assisting with bee-keeping duties, Richard Sebring is the principal horn of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, while Jane, also a French horn player, performs with the Boston Ballet Orchestra.)

“Finally, we got the queen – on the last branch,” Jane Sebring explained later in a phone call. “If you can get the queen, the others will follow, or if you get most of the swarm into the box, the queen will follow,” she said. The gas station swarm was only the second one the Sebrings have rescued. Their first attempt went more smoothly, she said, with “very orderly bees” that allowed themselves to be easily brushed into the bee-box.

Sebring has always been fascinated by beekeeping, she said, and in 2020 the pandemic gave her the time to pursue it seriously, initially through an online extension course from Penn State University, and more recently at weekly classes at the Bristol Apiary School in Bristol, RI, where beekeeper Lily Bogosian provides “incredible hands-on experience and mentoring.”

Swarming is part of honeybee colonies’ reproduction process, explained the Lexington Bee Company’s Alix Bartsch, who has kept bees in Lexington since the 1970s. “At this time of year, in May and June,” she said, “they’ll create some new queen bees and then the old queen will take half the bees and fly off into a tree or a bush. And that will be a swarm.”

Once the bees have found a temporary perch, or “bivouac,” said Bartsch, the swarm will stay there for anything from an hour to a few days, while they send out scouts to look for a permanent home, usually in a hollow tree or other cavity. “If we can catch them in the ‘bivouac’ stage,” she said, “then we can easily put them in a hive.” She guessed that the gas station swarm likely came from one of the hives she manages at the nearby Idylwilde conservation area and community garden.

Capturing swarms is important as honeybees in managed hives have a higher survival rate than in the wild, said Bartsch. Among the most serious challenges they face are infestation by Verroa mites, pin-head-sized red bugs that she calls “the number one enemy of honeybees,” loss of habitat and food sources owing to ever-expanding development, and widespread use of herbicides and pesticides.

Bartsch understands that swarming bees may alarm some people, but explained that in the swarming phase, they’re usually “very gentle and docile, because they’re not defending a hive.” Though she doesn’t recommend it, she has found by experience that it’s possible to put a hand right into a swarm without being stung. The most important thing to know, she said, is who to call when a swarm shows up. Then everyone wins: the swarm is safely removed and re-housed, and beekeepers are rewarded for their rescue efforts with a new hive-full of bees and a boost to their honey production.

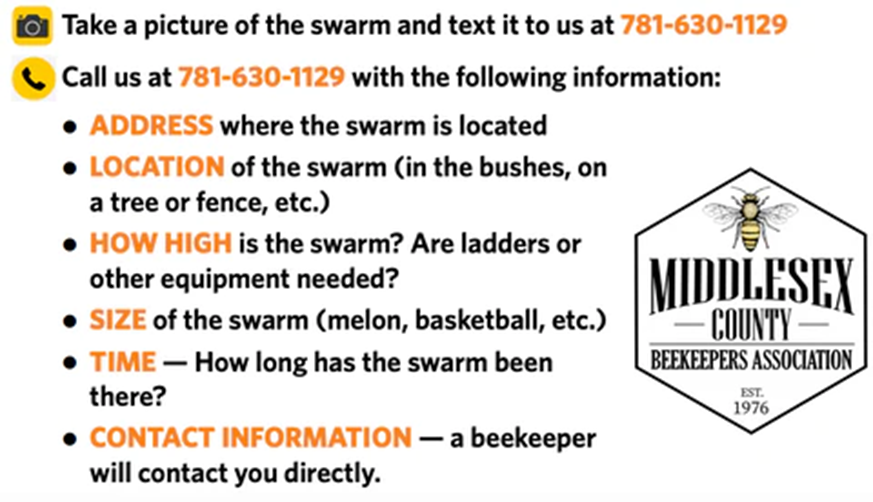

What to do if you see a swarm of honeybees: