The Impact of the Cold War on Lexington

In 1953, Lexington schools were good but certainly nothing special; ten years later, however, Lexington was lauded as a national leader in public education. Ironically, the pressures and anxiety of the Cold War transformed Lexington from a small, politically conservative community with average educational opportunities to an example of academic innovation and progress. In a decade, Lexington helped define educational reform, and the entire area has been a magnet for those seeking academic excellence. Certainly, many of us first moved here because of the schools!

The United States in the 1950s

Throughout the decade, the world continued its recovery from World War II, aided by the post-World War II economic expansion. ; After years of wartime rationing, consumers were ready to spend money—and factories made the switch from war to peace-time production. Post-war wages were high; people were moving into those grassy green suburbs, and the baby boomer generation was emerging. People sought a happy, serene family life seen on TV in shows such as The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.

On the other hand, there was a continuing tension known as the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the Western powers, as seen in the Korean War , the Cuban Revolution, the initial conflict in Vietnam, the launch of Sputnik 1, and increased testing of nuclear weapons with the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation. And here at home, the McCarthy hearings, designed to put a stop to “un-American” activities, led to unfounded accusations of communist activity and widespread fear. Western leaders believed that communism threatened democracy and communism needed to be contained.

In 1951, a new Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) was established to educate – and reassure – the country that there were ways to survive an atomic attack from the Soviet Union. One of the approaches involved schools. Teachers in selected cities were encouraged to conduct air raid drills where they would suddenly yell, “Drop!” and students were expected to kneel down under their desks with their hands clutched around their heads and necks. Many of us still know how to “duck and cover”!

Lexington in the 1950s

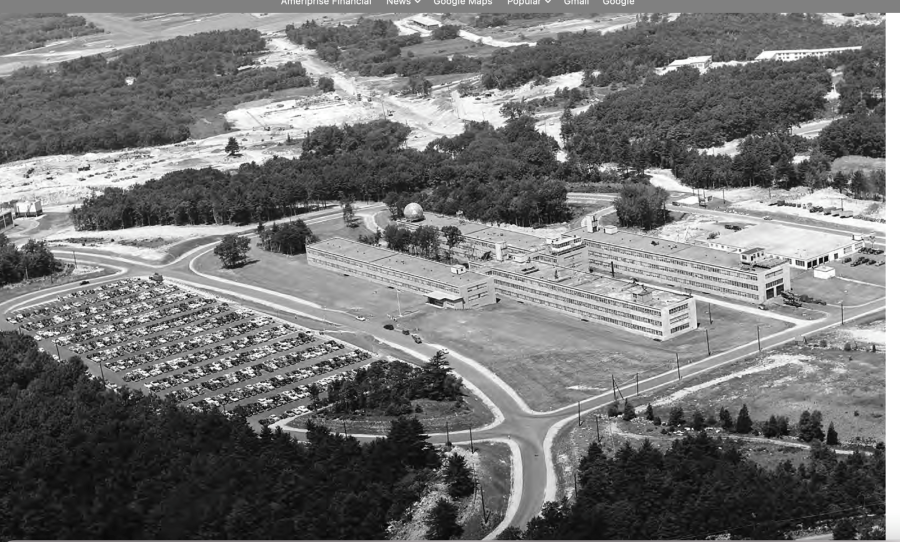

World War II had established the importance of radar. In 1945, the Army Air Forces aimed to continue some radar, radio, and electronic research programs. It recruited scientists and engineers from leading laboratories, and its new Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories (AFCRL) took over MIT’s test site at Hanscom Field Airport in next-door Bedford. By 1950, the Air Force was working closely with MIT to develop a new air defense system for the continental United States. Triggered by federal defense spending and technological advances, industrial development escalated along Route 128, attracting an influx of highly- educated engineers and academics involved with local universities or corporations such as Raytheon and Polaroid.

Many of those professionals moved to Lexington. With its history and rather rural location, it became a prime location for the young home buyer who wanted that newfangled ‘family room’ and backyard. Those professionals working or teaching around Route 128 found the housing prices reasonable at that time and Lexington’s proximity to Cambridge most appealing. From 1950-1960, Lexington’s population increased by almost 60, and the farms began to disappear.

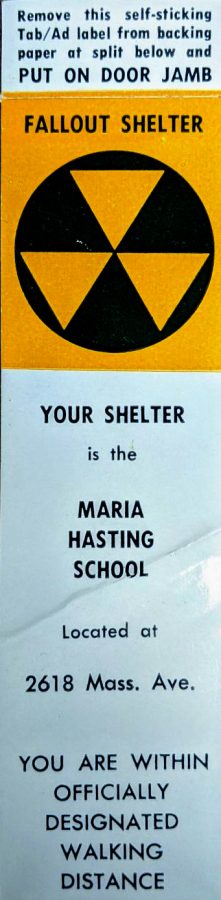

But even in rural Lexington, there was worry about the bomb. In 1953, our first air raid test aimed at all residents fizzled when the fire whistle malfunctioned and sounded for a full 10 minutes instead of a 3-minute series of short bursts. The same year, all residents were urged to participate in the Civil Defense Blood Typing program for use in personal emergencies and in time of nuclear attack. But by 1960, our Civil Defense radio network system located in Cary Hall had a chain-of-command operation covering the then-six precincts and two-way radio-equipped vehicles. In 1963, a Department of Defense survey of town buildings showed that there was sufficient fallout shelter space for all Lexington residents.

While the town was developing civil defense signals to warn of nuclear attacks and making plans to add fallout shelters to schools, the curriculum was being modified so students would see the importance of promoting democracy and the American way. An ‘American Problems’ class was created in 1951 for the purpose of teaching “the responsibility of the citizen to the Government.” According to the 1955 Town Report, history classes kept students in contact with the democratic way of life, taught them to study relationships with international neighbors, and to take responsibility for world peace.

While the town was developing civil defense signals to warn of nuclear attacks and making plans to add fallout shelters to schools, the curriculum was being modified so students would see the importance of promoting democracy and the American way. An ‘American Problems’ class was created in 1951 for the purpose of teaching “the responsibility of the citizen to the Government.” According to the 1955 Town Report, history classes kept students in contact with the democratic way of life, taught them to study relationships with international neighbors, and to take responsibility for world peace.

In 1950, Harry S Truman was president, and the Korean War began. The American economy was booming as was the birth rate. In Lexington, 19.6% of the workforce was classified as “professional and technical.” By 1960, that professional and technical workforce had grown to 28%. At that time, the workforce was mainly men; women were supposed to run the home and care for the children. Both parents aimed to raise their children so they would be successful adults; that included teaching children manners, taking them to Sunday school, and providing an effective education that would help them be successful. Newcomers to town began to push for change.

Changes in Outlook

In 1957, Lexington officials teamed with Arthur D. Little (ADL), an innovative Cambridge think-tank. The result was the Lexington Plan, where ADL would take one outstanding science teacher and work with that individual to design an effective science and technology curriculum that could be implemented in the lower grades. The goal was to stimulate interest in the children and to create a new generation of engineers. It was one of the first partnerships between industry and public schools. Other schools’ administrators started visiting Lexington to find more about establishing similar programs in their schools. That was just the beginning.

In October 1957, Russia launched Sputnik 1 The American response was a tremendous fear that we were falling behind the Soviets technologically, and led to rethinking our national education program in sciences. Lexington was ahead of the curve, however, already upgrading its science curriculum.

The same year, Harvard University Graduate School of Education proposed an R&D program with Lexington, Concord, and Newton schools known as SUPRAD (School-University Program in R&D) to test out new programs and research those already in progress. Harvard wanted to assess the efficacy of a Merit program and a Team Teaching program in Lexington’s Franklin Public School, which minimized the non-teaching duties of the instructor and encouraged creative thinking in the students through group learning and a series of specialist teachers.

The Lexington school system became a pilot school for a federally funded science program for public secondary schools, which used hands-on laboratory experiments instead of the traditional demonstration system. In 1959, the town hired several Elementary Science Coordinators to work with teachers to update the curriculum, work with children who displayed interest and arrange for guest scientists’ visits, among other tasks.

As computers became more popular, Lexington was a leader in incorporating technology into school curriculums. In 1966, it built a computer instruction lab. That same year, a Bolt Beranek and Newman server linked the Lexington lab to six other schools by phone. Lexington also established Advanced Placement in science at the high school.

Lexington had long been politically conservative. In the November 1960 national election, 7,474 residents voted for Nixon and 5,371 for Kennedy. But, its political stance was changing as its population grew through the addition of the scientific/engineering newcomers. Eventually, controversy erupted about the growing school budget and its impact on the tax rate, but by that time, Lexington’s schools were well established as being first-class. That fact continues to attract newcomers to town.

Editorial advice provided to the author by Anne Lee of Lexington Historical Society.