Fur Trapping in Lexington

L E A R N A B O U T L E X I N G T O N

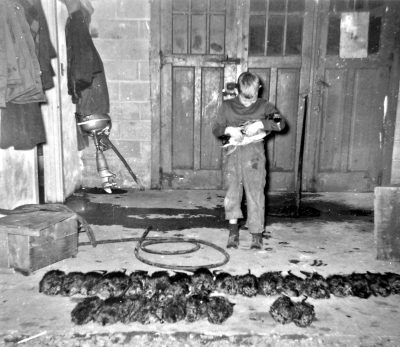

At age 8, Allen Buttrick, who moved from Locust to Bedford Street, would go to Tophet Swamp before school to set his traps. After school, he would pick up his shotgun and burlap bag, hunt pheasants and ducks, and check his traps again.

Allen says, “We would skin the rats in the cellar and hang them on the third floor. We used to eat them. We would fry them up – not bad eating.” Both he and his brother had 12 traps each.

His dad Gorham and friends were major muskrat hunters. On November 1, the trapping season opened. Before then, his dad and friends would strip swamp maple of its bark and cut stakes to put through the rings for the traps. Then they would take a 55-gallon drum and boil water with the bark and beeswax to eliminate any human scent. His dad would dig a trench in his corn fields for the carcasses, and the cats would head quickly to the fields.

They had a bumper year in the mid-50s, when each of them had 2,200 muskrat pelts. When they were ready, they would call in the fur buyer, who would price the pelts according to size, season, fur, and any damage. The average price of a muskrat pelt in 1951 was $3.50. Allen commented, “That was big money in those days, especially if you had 10 or 12 pelts. The price could go up to $6.”

The Past

Stephen Robbins of East Lexington introduced the fur-dressing business in East Lexington in the late 1700s. In 1783, he and his wife, Abigail Winship Robbins, bought a house at the junction of Pleasant and Main Streets (now Massachusetts Avenue in East Lexington. This location was ideal for their new fur-dressing business. The house bordered a large marsh that attracted populations of small animals and water for processing furs. Nearby, Robbins established a store where “they sold and traded West India goods for pelts and skins, which after being dressed and finished were again exchanged for goods, or sold.

In the late eighteenth century, Lexington, like most Massachusetts towns, was primarily an agricultural community with a population of about 1,000. Lexington was often the last stop for travelers before reaching Boston, which led to the establishment of numerous taverns along the heavily traveled routes. Many teams with four and six horses laden with produce passed through the town on their way to Boston or southern New Hampshire. There were also droves of cattle, swine, and sheep on their way to market or being driven to the backcountry for pasturage. Despite a lack of water power, various industries were established in town and especially in the East Village.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, East Lexington became the locus of manufacturing, entrepreneurial spirit, and prosperity in Lexington. Tanning, saw and grist mills, wheelwright and blacksmithing shops, and a shop that sold West Indian goods contributed to the economic vitality of the East Village, The dominant industry, fur-dressing is estimated to have employed over 300 people at its height in an era when the population of Lexington went from 941 in 1790 to 1543 in 1830. George O. Smith, in “Reminiscences of the Fur Industry,” states that: “men, women, and girls, who worked in the shops, and “many girls in well-to-do families, who found good revenue for ‘pin money’ in sewing furs and making capes and muffs in their homes.”

In the early nineteenth century. Stephen Robbins was the first to exchange pelts and skins for textiles and West Indian goods, which came to Boston from foreign ports. As a fur dresser, he tanned pelts from a variety of animals, and then cut them into strips that were made into muffs, boas, and other items. About 80 to 100 people worked in his factory. Smaller animals, like squirrels and rabbits, were trapped locally, but Robbins purchased most of his unprocessed furs, such as sable, fox, and bears, from Boston and New York fur dealers.

Processing raw pelts is known as “dressing.” The dressing of furs involves several steps, the exact number of which is determined by the particular fur being dressed. Generally speaking, a pelt is cleaned, softened, fleshed (extraneous flesh is removed), and stretched. The skin is tanned by a process called leathering. Stephen retired from fur dressing in 1810, and his son Eli assumed command, bringing in machines for some manual processes and hiring more people. In addition to fur dressing, he is credited with improving East Village and facilitating its growth as Lexington’s commercial center from 1800-1850. He built the first brick building in Lexington, which still stands on Massachusetts Avenue opposite Pleasant Street.

In 1833, Eli had Robbins Hall (aka the Stone Building), one of the United States’ earliest Lyceums, built by Isaac Melvin. Constructed at 735 Massachusetts Avenue, the building was a forum for lectures, preaching, and other meetings and a residence. Abolitionist/anti-slavery and temperance lectures and meetings were held here, and Charles Follen, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Thoreau all spoke during the mid-1800s. In 1891, Robbins’ granddaughter, Ellen Stone, sold it to the Town of Lexington.

They grew and prospered until the financial panic of 1837. At the end of the nineteenth century, their great-granddaughter, Ellen Adelia Robbins Stone (1854-1944), donated a large collection of clothing, costumes, and textiles to the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston. Most of the items had been used or worn by members of the Robbins family. The 1837 Financial Panic of 1837 forced Eli Robbins to declare bankruptcy. Concurrently, manufacturing in East Lexington began to decline. The advent of the railroad to Lexington in 1846 slowed the growth of East Lexington while stimulating the growth of Lexington Center.

The 1830 to 1850 period was one of great prosperity in East Lexington, largely due to the efforts and successes of Eli Robbins. Eli Robbins also erected a flagpole and observatory open to the public on the top of Mount Independence where the East Village Fourth of July celebrations were held. Robbin’s financial ruin, in turn, slowed the growth of the East Village. The coming of the railroad also had a huge impact, and by the end of the Civil War, the commercial center in town had permanently shifted to the Center Village.