Remembering Lexington Park

Many of the quotes used herein are from advertising brochures in the collections of the Lexington Historical Society Archives.

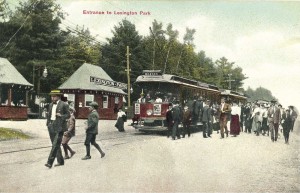

Today, the 48 acres on Bedford Street opposite Westview Cemetery are home to dozens of families. A regular residential neighborhood, very few passing through here would give thought to how it appeared one century ago. And still fewer would guess that this was where Lexington Park stood and operated for nearly two decades, during which time it was one of the premier such parks in the area — right up there with Norumbega.The history of the park is intertwined with that of the Lexington & Boston Street Railway. In 1901, the St. Railway. purchased the “picnic grove” known as Boardman’s Grove, and opened it in 1902 as Lexington Park: a combination picnic destination, restaurant, casino, performance area, and the perfect place for fresh air outings. The idea was to draw more people out to this part of the Lexington-Bedford trolley line.

A 1911 booklet, The Sunday American Summer Outing Trips, comforts the common man: “Don’t feel envious or sad because you can’t afford an automobile, or long expensive trips over the steam railroad lines to distant points. … You have the people’s auto — the trolley car — which will take you to as fine scenery … as you can find on the most expensive trips.”

The Street Railway, in addition to hiring a park crew and special policemen, took on a manager for the operation. His name was John T. Benson, and it was he who brought the animals and birds for a “zoological garden” which he opened on the grounds. This zoo quickly became the feature attraction of the park.

Benson was born in 1871 in England and, in his early years, had left home with a captured bear and his mother’s wedding dress and joined the Bostock animal show, a traveling circus. Here, he gained his skill with animals, which he employed for the rest of his life. He immigrated to America at the age of 20. When he arrived in Lexington about 1902 for his new job at the park, he boarded at the George C. McKay house on the corner of Sherman and Sheridan Streets. His business partner, Winifred Griffen, lived around the corner on Fletcher Avenue. The McKays treated Benson as part of their family, and George’s granddaughter Evelyn Hooper Stenstream later recalled, “J.T. was a funny, quirky man but I loved him dearly. He was like another grandfather.”

“Mr. Benson,” she continues, “was the consummate showman (from his early days with the circus), but every penny he took in at the gate, he turned back into the business.”

The visit to Lexington Park would almost always begin by boarding an open car on the Street Railway. Some of the town’s older residents can still recall a ride up the Avenue and then up Bedford Street in their very earliest years. The car then turned into the park entrance, about where Perham Street (Bedford) is today. Bearing to the right, the park’s main road somewhat followed the area of today’s Woodland Road.

When the Street Railway bought Boardman’s Grove, they certainly chose the right property. Full of mammoth pine trees, that natural beauty led to slogans such as “Listen to the Murmur of the Pines” and “Breathe the Exhilarating Pine Ozone.”

There were many opportunities for exercise and fun. For example, an “open-air roller skating rink … equipped with the latest improved ball-bearing roller skates” allowed one to skate for 365 feet straight. Also here were a baseball park, athletic field, and bowling alleys.

Amongst all the exhibits at the “large, clean and instructive Zoological Garden,” perhaps the most popular were the bear-pits. They claimed to be the “most picturesque” such scene in the world. However, one man is said to have stuck his arm in the cage and received a scratch which later became infected, resulting in his death. Nevertheless, the bears continued to be the crowd favorite. One cub, “Young Bruin,” was particularly adorable and would walk on his hind legs while holding the trainer’s hand. Two cubs, born in July of 1903, were given the dignified names of President Theodore Roosevelt and Kaiser Wilhelm. Historian Richard Kollen notes that “since this event predates the famous hunting incident that led [to the stuffed bears’ name] “Teddy’s Bears,” the Lexington Park Teddy may be considered the first Teddy Bear.”

Other animals on display included “the finest collection of herbivorous animals in New England”: camels, elk, Virginia deer, white fallow deer, axis deer, buffaloes, zebus, yaks, aoudads, and nilghai.” There were also wolves kept here for a short time, though they escaped through an attendant’s error and caused much worry in the neighboring towns for months. Separate buildings included the Monkey House and Aviary, where there was an extensive bird collection.

The list of attractions goes on: the impressive flower gardens should be noted, as should the open-air “rustic theatre.” Billed as “the finest rustic theatre in America,” this was “where high-class performances, consisting of vaudeville, operas and musical comedies, are given every afternoon and evening.” Three thousand people could fit into this audience, all seated in comfortable chairs. And about 1913, an open-air dance hall was unveiled, which proved very successful. Also separate from this was a Music Court featuring performances from a ladies’ orchestra.

Standing high above all this activity was the lookout tower, from which the Wachusett Mountains could often be viewed. And it was most certainly high up, being of an elevation 135 feet on top of the Bunker Hill Monument.

Picnic capabilities were a main advertising point, as one brochure calls this “The Picnic Center of Massachusetts.” Let us not forget there are 48 beautiful acres, thus lending itself to the entire staff’s company picnics as well as church outings. In addition to the customary tables for smaller parties, free kitchen use was offered as well. If one had a mind for a regular dining experience, there was a restaurant (The Colonial) and the Casino, “both in charge of a capable caterer.” The menu specialty was a steak dinner. Contrary to modern-day terminology, the casino was not about gambling. Rather, it was full of gastronomic guilty pleasures: homemade ice cream and popcorn, confectionery, and “temperance drinks” among them.

Benson’s Country Store, the park’s souvenir shop, was adjoining this area. Many plates, cups, and other types of souvenir china still survive, bearing an image of the park or the familiar Benson’s name. Also in this area was the electric arcade, for the entertainment of the “little ones” or “little folks” (as the brochures call them), who could also enjoy the playground, carrousel, and swings, if they could ever be dragged from the zoological exhibit. Billing themselves as having “no dangerous devices,” this park was “a children’s menagerie: Nature’s Recreation Grounds.”

Remarkably for the time, there was a devoted Women’s Building, constantly presided over by a “neat and obliging matron.” Ladies could use the free lending library, and there was an area for their children to take a nap. There was also a “spacious veranda, fanned by the cool breezes and shaded by the tall pines and surrounded by fragrant flowers, with plenty of rocking chairs and tables, where Women’s Clubs and afternoon whist parties hold sway.”

In its heyday, the park generated so much traffic on the Street Railway — especially on Sunday afternoons — that barely enough trolleys could be brought out from the car barn to accommodate these people. And when the park got particularly busy, the “firemen,” who kept the coal boilers stoked at the Street Railway’s own power plant (today the K of C Hall), had a very hard time keeping them adequately fueled.

In the winters, Benson and his partner Winifred Griffen would take most of the animals to a park in Cuba to enjoy the warmer climate. A few of them, however, were kept during that season in a building near the power plant. They would return for the re-opening each season in mid-June, remaining until Labor Day. Speaking of the wintertime, Benson would usually issue an annual weather prediction, which he based on the behavior of his extraordinary livestock. According to a later account in the New York Times, Nov. 19, 1937, after Benson had set up shop in New Hampshire: “John T. Benson, animal farm manager, today warned that this would be a “short but cold Winter.” … Mr. Benson asserted that the tails of squirrels had not yet feathered and that beavers had not yet begun to store their Winter wood, nor muskrats their food.” Apparently, Benson was well-linked with his animals.

His obituary later stated he “made more than thirty trips to India and Africa to obtain animals for zoos throughout the country.”

It was about 1920 or 1921 that the park’s business had so dwindled it was forced to close. Those powerful men who owned the automobile industry and manufactured buses used their political power to lean on the right people. And by 1924, the street railway in Lexington had become “trackless.” A sign of this appeared in the mid-1910s when the park brochures first showed automobile parking spaces. So Benson, after about eighteen years here as manager of the park, moved on.

Benson moved some of the animals to Norumbega Park (also owned by the Street Railway). But by 1922, he had gone up north to Hudson, N.H. There, he began a quarantine farm as a stop for animals brought to this country for various zoos. When local folks began to take an interest in the strange noises coming from there, it soon became open to the public as Benson’s Wild Animal Farm. Supposedly, Benson’s mother’s wedding dress (which he had taken with him to the circus in England) was on display here. This “Strangest Farm on Earth” survived three ownerships and many happy decades for visiting New Englanders until it closed in the late 1980s.

From then until the early 2000s, the Hudson farm was the target of many vandalisms. However, in 2001 and ’02, a plan was formed to preserve this site. Restoration has since begun on the property, which is now known as Benson Park. A local organization, the Friends of Benson Park, have been responsible for much of this work.

Though not nearly as well-preserved as the Hudson, N.H. farm, some remnants of Lexington Park are still today. The old bear pits still survive in a private backyard, a stone fountain (supposedly for elephants’ refreshment) is now used as a flower planter, and the occasional archaeological find or two (such as a century-old old root beer bottle) have surfaced.

The Women’s Building is the only original building still standing from Lexington Park. It once bore an impressive veranda facade, and in the “front yard” was the advertised Capt. Parker Spring is reputedly from a very clear and natural source. Today, the house stands right on Woodland Road over the Bedford line, and the Parker Spring no longer graces the beautiful hillside. It still retains, however, its Craftsman architecture, which could once be found in the numerous other pieces of the Park enterprise.

About 1940, Benson and Griffen, his longtime business partner, finally split. Falling ill a short while after, “J.T.” Benson died September 18, 1943, at age 72. Despite his notable positions, such as first curator of the Franklin Park Zoo, and “American representative of Carl Hagenbeck, Hamburg, Germany, at that time the largest importer of wild animals in the world,” Benson died absolutely penniless. As has been said, he put every bit of profit back into his enterprises, so great was his love for his work. In his final days he had become dependent on the McKay-Hooper family with whom he had once lived in Lexington.

Today, very few Lexingtonians remember John T. Benson. There are some residents of the Lexington Park neighborhood who are aware of this remarkable man, though as a town, this piece of our history has been largely forgotten — and in a rather short period of time, too. In the past ten years, many members have been lost from the generation who had visited the park as children. Three years ago, an article in the Minuteman about the Lexington streets named after specific people appeared. A “John Benson Road,” was built in the 1990s on the former park property. Minuteman staff could not find any trace of the man and concluded that this road was named after a member of the Mendon, Mass., militia of 1775. This symbolizes, perhaps, the increasing unawareness of Benson here. However, when he went up north to Hudson, it was not for good.

“Mr. Benson left a most confusing will,” Evelyn Stenstream remembered. One of its stipulations was that he be returned to Massachusetts from his Hudson, N.H., residence. He directed that he be buried in Westview Cemetery in North Lexington, in a neighborhood that perhaps his heart had always known as “home.” A tireless worker in life, today he rests beneath a clump of pine trees, with cones scattered around his marker. Still today, he listens to the murmur of the pines, as he once did so many years ago.

From this vantage point, J.T. Benson looks across Bedford Street and keeps watch over his former domain. And all day long, like clockwork, the MBTA bus passes by — a sad reminder of the end of the trolley line, which heralded the end of Benson’s Lexington Park.