Marjan Kamali’s The Stationery Shop: A Story of Love, Loss and What Happens After

T ehran, 1953. As the Iranian capital simmers with political unrest, two teenagers meet and fall in love in the calm sanctuary of Mr. Fakhri’s stationery shop.

Among shelves stacked with pens, paper and volumes of classic Persian poetry, Roya Kayhani and Bahman Aslan embark on a lightning courtship. But the course of true love ends in a baffling separation on the very day of the CIA-backed coup that overturns the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh.

Lexington author Marjan Kamali’s second novel, The Stationery Shop, is a story of love, loss, and resilience set at a pivotal point in Iran’s history. The narrative opens in 2013, when 77-year-old Roya, long married to an American and living in a New England town much like Lexington, learns by chance that Bahman is being cared for in a nearby nursing home and makes an appointment to see him.

Decades after they parted and half a world away from the Tehran of their youth, Roya and Bahman have many questions for each other about what really happened in that hot, tumultuous summer. The answers emerge from a buried family history of shame, pain, and thwarted love.

Thickening the Plot

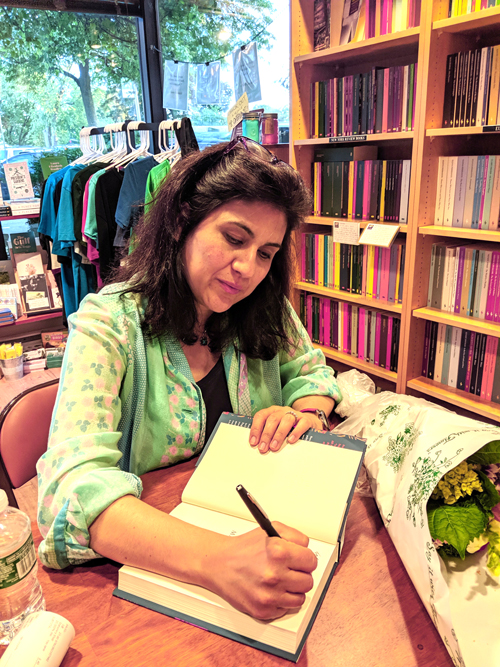

“I’ve always admired writers who write well, and plot well, and I’ve never felt those things were mutually exclusive,” said Kamali in a recent conversation. Her 2013 debut novel, Together Tea, a Massachusetts Book Award finalist, was a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novel with a straightforward narrative structure. For her second novel, Kamali wanted to stretch herself by concocting “ a really damn good plot, with twists and turns, surprises and layers.”

Judging by favorable notices in publications from The Wall Street Journal to Newsweek and Kirkus Reviews, she has succeeded. “Readers will be swept away,” says Publishers Weekly, praising Kamali’s vivid evocation of “the loss of love and changing worlds.”

“They say there are two kinds of writers – plotters and pantsers,” said Kamali. Plotters know where the story is going. They make an outline and use index cards to track events and characters. Pantsers fly by the seat of their pants. She puts herself firmly among the latter: “When I start the day, I don’t know where it’s going,” she said.

What that means, for a ‘pantser’ trying to develop a complex plot, is “a lot of reworking.” Kamali used her first draft to figure out some major plot points, but there were many unanswered questions. “I knew Bahman had to disappear,” she said, “but I didn’t know why he disappeared.”

For Kamali’s literary purposes, Bahman had to disappear so that he could write letters to Roya during their separation. In homage to the love of literature that is embedded in the Persian psyche – a love shared by Roya and Bahman – she has them exchanging love letters between the pages of books in the stationery shop.

Composing Bahman’s letters allowed her to write for the first time from a male point of view, something she had not attempted in Together Tea. “The letters turned out to be a rich plot device,” she said, “but it’s difficult to write love letters without sounding cheesy!”

How We Talk About Iran

Kamali longs for the day when negative coverage of Iran disappears from US headlines. But until that day, she said, like many Iranian Americans of her generation she feels a responsibility to show “a fuller, richer picture – to tell the stories of the people behind the headlines.” In spite of the current repressive government, she said, Persian culture is “a joyful culture – colorful, vibrant, full of zest for life.”

Born in Turkey to Iranian parents, as a child, Kamali lived in Kenya, Germany, Turkey, Iran, and the United States. Although she only lived in Iran for five years, her home was always an Iranian home, no matter where her diplomatic family happened to be living.

In her first novel, The Stationery Shop, Kamali gives vivid glimpses of Persian food, manners, and customs. “Food is so much a part not just of the culture, but of every person’s character, almost,” she said. But although her descriptions of jeweled rice and chicken khoresh make the reader want to reach for a Persian cookbook, the cooking scenes always serve to develop relationships and move the story forward, as when Roya introduces her American boyfriend Walter to the joy of cooking with cinnamon, cardamom and saffron.

To get a sense of Tehran in the early 1950s, Kamali interviewed older family members. Her father proved an invaluable source for the city’s geography, crucial to the plot, recalling the names of streets and squares. (To Kamali’s surprise, these were all fact-checked by her copy editors, by reference to old maps.)

“From my father, the other thing I got was the feel of the city,” said Kamali. From him she learned what people were eating in the cafes, the kind of coffee they were drinking, the clothes they wore, and the music they listened to.

The period details enliven memorable scenes, as Roya tastes her first espresso coffee in the chic Café Ghanadi, learns to dance the tango with Bahman to gramophone music at the house of his wealthy friend Jahangir, and watches the Italian movie The Bicycle Thief in the gold and red-plush splendor of the Cinema Metropole. From such vignettes, Kamali creates a portrait of a city with a flourishing cultural life, alive to new influences and open to foreign ideas.

Democracy Derailed

Kamali’s love story unfolds against the backdrop of faction-fighting that ended in the overthrow of democratic rule in Iran in a coup engineered by US and British intelligence services on August 19, 1953. At stake was the future of the mainly British-owned oil industry, nationalized by the Iranian parliament in April 1951, and a desire to neutralize the perceived threat of Communist Russian influence.

Prime Minister Mossadegh was overthrown, and the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who had fled to Baghdad in his private plane after an abortive coup attempt on the night of August 15, was restored to the Peacock Throne.

“A lot of people think of 1979 as the turning point for Iran, and in many ways it was,” said Kamali. “But 1979 wouldn’t have happened without 1953.” The Shah’s increasingly authoritarian rule led to riots, strikes, and demonstrations, the return to Iran of Islamic clerical opposition leader Ayatollah Khomeini, and, in April 1979, the proclamation of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

“The coup is still a very contentious subject,” said Kamali. She dramatizes the political divisions that extended even into schools, by showing one of Roya’s classmates, a girl with communist sympathies, being assaulted by police with a water hose as she leaves school. Bahman and Roya’s father, Baba, bond over their shared devotion to Mossadegh, and Bahman is beaten up by the Shah’s police at a pro-democracy demonstration.

To give an accurate picture of the events of August 1953, Kamali consulted published sources, including Stephen Kinzer’s All The Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. She collected stories from relatives and family friends who lived through the upheaval. They shared a feeling of disillusionment, “a sense of losing a future and becoming a different country,” she said.

Many readers have told Kamali that they knew little, if anything, about the 1953 coup, but that they have been inspired by the book to do their own research.

A Lot of Crying

“I’m hearing from readers that there’s a lot of crying going on,” said Kamali. “I hope it’s a healing kind of crying!” Through her website and on social media, readers are telling her that Roya and Bahman’s story has helped them put their own first love into perspective. “I get a lot of emotional catharsis responses,” she said.

Some readers have been inspired to write letters to long-lost boyfriends and girlfriends. People have written privately to share their own love stories, and one reader even made a playlist of love songs for Roya and Bahman, including Iranian and American songs from the 1950s.

In the end, Roya and Bahman are not Romeo and Juliet. Though seared by their intense youthful love, they do not perish. Wounded but resilient, they go on to have long lives full of other joys and sorrows. As she looks forward to taking the book on the road at Fall literary festivals, Kamali stresses the importance of that message: “I really, really wanted to show that life goes on, and on, and there is no one love, one soul mate, no one style of love,” she said.

For more Information, visit marjankamali.com