Pandemic Perspectives

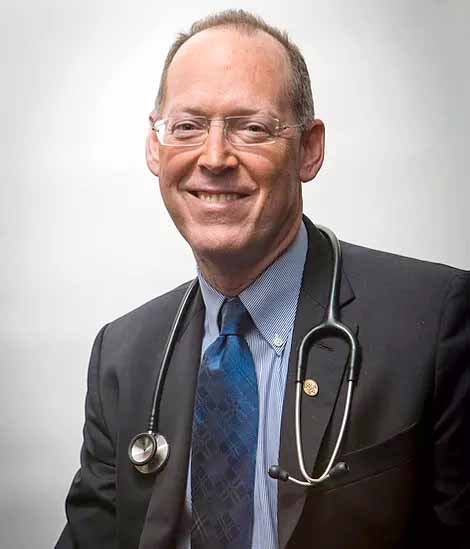

Renowned physician and humanitarian Dr. Paul Farmer will speak on The Color of COVID: Reflections on Pandemics Past and Present, in the Cary Lecture Series, at 8:00 p.m. on Saturday, April 24, via Zoom. (For a link, go to the website: carylectureseries.org)

It’s a topic that is never far from Farmer’s mind. Since first setting foot in Haiti as a student in 1983, and being appalled by the lack of basic medical care, he has become one of the world’s pre-eminent investigators and challengers of inequalities in health at home and abroad.

Once described as “a world-class Robin Hood,” in 1987, while still a student of medicine and anthropology at Harvard, Farmer co-founded Partners in Health (PIH) with friends and allies Ophelia Dahl, Dr. Jim Yong Kim, Todd McCormack and Tom White. Since then, this Boston-based non-profit has provided health services to some of the world’s poorest people in ten countries including Haiti, Peru, Liberia and Rwanda, using novel community-based strategies for treatment and care.

Among the core principles of PIH, as stated on the organization’s website, is this: “It is our moral call to action to expose social injustice and work toward correcting those systemic forces that create inequalities, no matter how impossible or challenging this task might look.”

The daily struggles, successes and setbacks entailed by such a high-sounding – and sometimes downright dangerous – mission are brilliantly captured in Tracy Kidder’s best-selling biography of “Doktè Paul” and PIH, Mountains Beyond Mountains (Random House 2003.) Farmer emerges from Kidder’s reporting as “one of the most provocative, brilliant, funny, unsettling, endlessly energetic, irksome, and charming characters ever to spring to life on the page,” as he embarks on an epic quest that takes him from “the halls of Harvard Medical School to a sun-scorched plateau in Haiti, from the slums of Peru to the cold gray prisons of Moscow,” wrote Jonathan Harr, author of A Civil Action.

Now a notable figure in those Harvard halls, as Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Farmer has accumulated numerous awards. His most recent accolades are the Public Welfare Medal given by the National Academy of Sciences in 2018 – its highest honor – and the $1 million Berggruen Prize for 2020, given for his leadership in the coronavirus pandemic.

Now a notable figure in those Harvard halls, as Kolokotrones University Professor and chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, Farmer has accumulated numerous awards. His most recent accolades are the Public Welfare Medal given by the National Academy of Sciences in 2018 – its highest honor – and the $1 million Berggruen Prize for 2020, given for his leadership in the coronavirus pandemic.

“[Farmer] has reshaped our understanding not just of what it means to be sick or healthy, but also of what it means to treat health as a human right and the ethical and political obligations that follow,” Kwame Anthony Appiah, chair of the Berggruen Prize committee, and a professor at New York University, told the New York Times.

Farmer had just finished his most recent book, Fevers, Feuds and Diamonds: Ebola and the Ravages of History (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2020) as the coronavirus pandemic took hold in Europe and the United States in Spring 2020. The book combines his first-hand account of the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in the “clinical deserts” of upper West Africa, with a deep dive into the history of the region, crippled by five centuries of what Farmer calls “rapacious extraction – of rubber latex, timber, minerals, gold, diamonds and human chattel,” by European colonial powers.

The lethal toll of Ebola in countries like Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, Farmer concluded, was not because the virus was inevitably fatal – very few infected Americans and Europeans died –but because those countries lacked health care essentials like intravenous fluid replacement and dialysis.

Comparing COVID-19 with Ebola, Farmer told me, he predicted early on that as always, there would be local particularities, but that “most of the big dramas” would follow a similar pattern. “We’re going to see resistance to social distancing, to precautions of all sorts, we’re going to see refusal of people to turn their backs on their family members when they’re sick or dead,” he said.

One of Farmer’s targets in Fevers, Feuds and Diamonds is what he calls the “clinical nihilism” of some public health policy-makers and practitioners who claim that it is “not feasible, not cost-effective, not sustainable” to treat certain people. “It’s like, they’re just too poor to help,” he said. “And that’s bullshit of course – we’d better give up the ghost when we say publicly that people are too poor to treat.”

What soon became clear was that a major problem in the US response to COVID was another kind of nihilism. Farmer calls it “containment nihilism.” That is, the failure to deploy systematically “the staple interventions of public health in a pandemic or epidemic,” including mass testing, contact tracing, masking and social distancing.

It’s hard even to register the toll of “our uniquely poor performance as a wealthy and medically endowed nation,” he said. “We don’t have a safety net that would prevent people falling into the abyss – and they did. We knew it would be bad, last year, in the US, but it’s kind of worse than I would have thought,” he admitted.

Then, in what he self-mockingly called a “reliable swerve to the optimistic” he said he finds it heartening to see how the Biden administration is acting to provide relief. “I’m not just talking about the vaccine rollout – which is going fairly well,” he said. “I’m talking about the safety net extensions, unemployment insurance, eviction prevention, just a transfer of some of the vast wealth of our nation to people who need it most.”

With more than 30 years of experience partnering with governments around the world to strengthen health systems and lead successful responses to infectious disease outbreaks, such as Ebola, tuberculosis, and HIV, Partners In Health is well equipped to be a global leader during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since March 2020, PIH has led targeted interventions world-wide to respond to urgent needs, such as training contact tracers and providing stocks of PPE and rapid tests, while also strengthening health systems so that they can better respond to future pandemics.

I asked Farmer about questions raised in a recent Boston Globe article (March 28) about PIH’s efforts close to home. The article quotes several public health officials in Massachusetts unhappy with the Baker administration’s decision to contract with PIH to run the Commonwealth’s contact-tracing program, at a cost of $130.4 million by the end of June 2021.

Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Health Officers’ Association and Norwood’s health director, is quoted as acknowledging that help from PIH was vital in the early stages as the first wave of the pandemic hit the Commonwealth. But she would have liked to see some of the money spent on building “something more sustainable” to prepare local departments to take over the job.

“I’m very sympathetic to that critique,” said Farmer. “These [public health officials] are people whose feelings and energy matter a lot to me.” But he thinks the criticism is unrealistic, borne of frustration at chronic underfunding of the public health infrastructure.

The middle of a pandemic is not the time to be restructuring the state’s public health system, he said, although he strongly supports “massive investment” in the US public health bureaucracies. “Like a lot of PIH people,” he said, “the way I see it is that we stepped in in the middle of an emergency and put our hearts and souls into protecting the people of Massachusetts.”

In spite of his “inviolable optimism,” Farmer admitted to sharing the anxieties of his friends and colleagues Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Rochelle Walensky, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “If we take our foot off the pedal now – with social distancing, mask-wearing, contact tracing – what do we have in our arsenal to slow down transmission among the unvaccinated?” he wondered.

Farmer was moved by Walensky’s emotional plea during the White House COVID-19 Response Team briefing on Monday March 29. Acknowledging the new sense of hope offered by the vaccine rollout, she admitted to a sense of “impending doom” In the face of rising numbers of coronavirus cases, hospitalizations and deaths, and begged people not to abandon their protective measures. “I was grateful that she spoke in such poignant terms,” said Farmer. “We will get through. The question is, what’s the tally on the way out?”

To learn more about the work of Dr. Paul Farmer and Partners in Health, visit the website: https://www.pih.org

A 2017 documentary featuring Farmer and PIH, Bending the Arc, is available on Netflix.

LexMedia records all the Cary Lectures. Visit the website: https://www.lexmedia.org. You will find the Cary Lecture Series on the On Demand tab. Please note that posting sometimes takes a couple of weeks.