Q and A with Cara Bean: Comic Author, Former LHS Teacher, and Champion for Teen Mental Health

C ara Bean is the author of the graphic novel here i am, i am me: An Illustrated Guide to Mental Health, and taught art at Lexington High School from 2005 until 2018. While at LHS, she became inspired to use comic art to engage teens about mental health. Cara is passionate about drawing and believes that the simple act of doodling on paper can lead to the investigation of complex ideas. Her current work includes interactive workshops and other projects helping people of all ages and backgrounds tap into their creativity for introspection, playful storytelling, and growth. She grew up in Weymouth, MA, has an MFA in Drawing and Painting from the University of Washington in Seattle, and received a certificate in cartooning from the Sequential Artists Workshop in Gainesville, Florida.

In recognition of Mental Health Awareness Month, Xena Thadar, an LHS student member of Sources of Strength – a peer-led, strength-based suicide prevention program – and Elliott Gimble (an adult advisor) spoke with Cara about her life and her work in promoting mental health through writing and art. Her comments have been edited for clarity and space considerations.

“I tried to make a comic that spoke directly to the young person and to make that information really easy to break down and process, about the questions of anxiety, about substance abuse and addiction, and, most importantly, how to get help…”

LT: When did you first know you wanted to be a professional artist?

CB: I was always making art from a very young age, and it was what I was best at. I think it wasn’t until the end of high school, until I went to art school, that I met real artists, and I saw “they have jobs, and cars, and it’s amazing! They’re able to live their lives as artists.” That showed me it was possible because I came from a family where there were nurses and mailmen and teachers, but I didn’t know any artists.

LT: Were your parents supportive?

CB: Yes. Being a teacher here in Lexington for so long, I realized how much my parents really just let me do what I was interested in. I felt really lucky, because I met students who felt all this pressure around grades and their futures and I didn’t understand that. I had been given this flexibility to pursue my passion; my parents just wanted me to “be a good person, pay your bills, but do what makes you happy.”

LT: What inspired you to write a cartoon book about teen mental health?

CB: That’s a big question. I was a high school art teacher here and had studied art for a long time. However, I didn’t feel like I knew enough about mental health. I would notice my students would be struggling, even though art classes are something more relaxed, and the feelings are allowed to be in the room. So I would see in their work that they were troubled, or I would see it in the crumpled-up things in the corners of the room, or when an artistic or quiet kid might choose me as the adult that they trusted. I always felt like I needed to know more about how to help them.

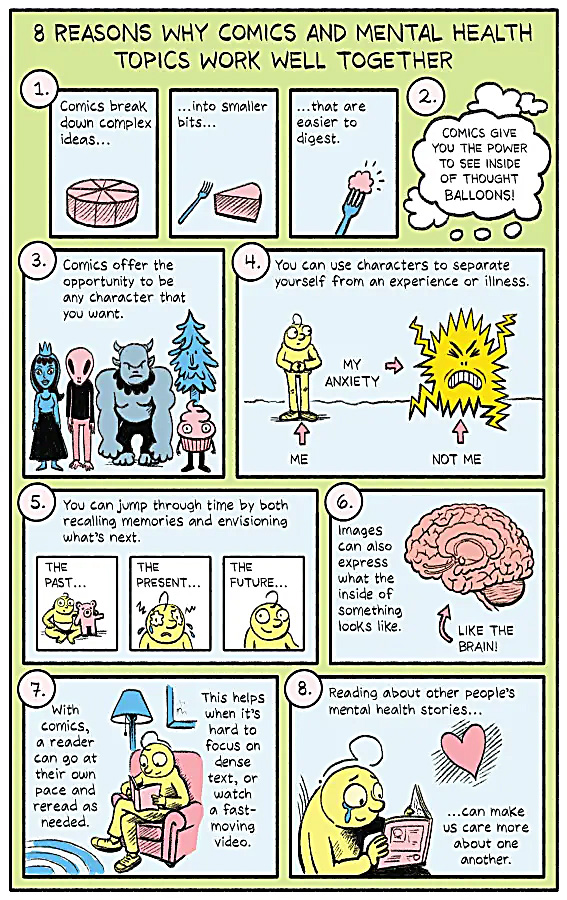

So, any time there was a training for educators about mental health, I would sign up. And because I’m a cartoonist, I draw out all my notes in sketches and doodles because that’s how I process and learn. I have to draw or even just rewrite things to help me learn, and I would come up with symbols for symptoms and break down ideas.

Other people saw my doodles and loved them and said, “Can I borrow that? That’s really helpful, I like how you are drawing it.’’ Over ten years’ time, those became a little ‘zine called Snake Pit, which is still on my website. Eventually, it came into the hands of someone in the publishing industry and became the Snake Pit mini-comic, geared toward adults working with young people. But the publisher challenged me and she said, ‘I like what you’re doing here, and I have a twelve-year-old daughter: I’d love to see a comic that spoke directly to the young person, and have you ever thought about that?’ And that’s where this book came from.

I tried to make a comic that spoke directly to the young person and to make that information really easy to break down and process, about the questions of anxiety, about substance abuse and addiction, and, most importantly, how to get help or reach out if you need it.

LT: How long did it take you to write and illustrate this book?

CB: I was trying to do it and teach, and it was not going well, so I decided to take a year out to do it, and at the end of that one year, I had barely cracked open what it could be, so I did not return to Lexington. It took six years to finish; I started it in 2018 and the book came out in 2024, with the help of many, many wonderful people. It was certainly a work of collaboration with therapists, neuroscientists, researchers, addiction specialists, many readers and editors, and young people, who would read and give me notes back. So I think that’s another reason why it took so long; there was a lot of editing and getting it just right.

LT: What was most challenging during that process?

CB: I think when I first started to do this book, I was nervous to be in it, honestly. I was trying to create a narrative, and it kept imploding or blowing up in my face because it wasn’t honest. I realized as a teacher, when you’re authentic and you’re really speaking to your students, that’s when they can hear you. But if you’re coming up with a story, you might be entertaining for a quick little moment but you can’t get into the type of subject matter that is in this book. So at the beginning, I really resisted being in the book. Once I was ok with me in the book, talking to the reader, it started to come together.

And then when the pandemic happened! I moved in with my parents; my father was very sick, and so my Mom and he needed help anyway. I would work in the basement underneath their home, creating it, and then come upstairs and help them, and go downstairs. I think it was a gift in a way that it was a very focused time. There was nothing else I could be doing, but at the same time, it was emotionally heavy, dealing with my parents, and also scary that the pandemic was happening.

LT: One of the most impressive aspects of the book is how you were able to weave in your own story while keeping focus on the subject and the fact that everyone is on their own journey. What was it like for you to walk that line?

CB: It’s definitely more than I would have talked about in my classroom. Being the author gave me freedom and a little distance because I’m not actually your teacher. That said, I’m a human and am still a teacher at heart, where I wouldn’t want to be trauma-bombing my audience. I’m not going to go too far over the line to make you uncomfortable. I just want you to know, “hey, I was a young person, too, and I’ve gone through things”. I think that makes you trust your author more.

I also love that this book is not like a graphic novel in the way that it’s not a page-turning story that you’re excited to get through the whole thing. You don’t have to read the whole thing as it is, you can pick it up and put it down. It’s kind of an encyclopedia of mental health, but the pictures make it easier to read than a textbook, and more like a comic, but it’s still a lot. So I felt that having those authentic, true-from-my-life stories in it, which I call “the pink pages,” connect me to the subject matter but also give the reader a break from vocabulary, science content, or just heavy conversations.

LT: The book opens with the topic of Stigma; why did you choose that topic to be first?

LT: The book opens with the topic of Stigma; why did you choose that topic to be first?

CB: That topic wasn’t originally at the beginning but one of my editors said “Why don’t we put this up front?,” and I’m really glad we did. When I do school visits now, I read the stigma chapter, and sometimes I can get people to play the Stigma Monster. It just breaks open the topic of mental health in a broad way. It also signals “OK, we’re going to talk about things that are stigmatized,” and we can break the tension in that and make it a cartoon and playful.

LT: Your book’s audience is 12-year-olds and older, were there times when you cut things out because they seemed to be getting too intense?

CB: Definitely. This is something that is good for people to know about the cartooning and comics community: self-publishing is embraced and people are just excited to put their work out there, and you get immediate feedback. I’ve been doing that for 15 or 20 years now. I’ve made little things and taken some swings and missed, and people respond it’s a little too much or upsetting, so I’ve developed a voice over time.

The character who’s the therapist in the book, Michael Safranek, is a British therapist, also involved in comics, and he uses that as part of his practice. We met through an organization called Graphic Medicine which is a group of people who use comics to heal, or help, or educate. He was an early reader of some of the chapters and had some great edits about various pieces, especially the chapter about suicide prevention. As I started going through my content, he was the one who said, “You know, let’s talk about it if it’s a friend or someone you worry about first. How would you help that person? And after that, let’s consider if we were ever in this position and what would we need or what could we do?” I was so grateful for that guidance.

There were a lot of other people that were readers and helpers in that way. And that’s one thing I like to tell people who are making things is that you should never do it alone. You should invite as many educated, knowledgeable people as possible to help you do something. Because when you are doing it alone, you may feel overwhelmed or you feel like you’re going to make a mistake or hurt somebody. But if you have a good team, then you can feel better that it’s going to be more sensitive to your readers if you have lots of different people read your work. And then listen to them and incorporate what you learn.

When I first started teaching at Lexington, I got to be friendly with some of the guidance counselors, and I was amazed at the conversations they were having with students and that they could plainly ask, “Are you thinking of killing yourself, and do you have a plan?” And I would say, “You can ask that?” and they would say, “Yes, you have to ask that!” I didn’t know that was a thing, and then in these trainings, I learned that it doesn’t hurt somebody to bring up suicide, it doesn’t hurt somebody to talk about these things. It actually relieves them so they know they can talk about it and then pursue help if they need it. So once I understood that was important, then it was really like a piece of the puzzle. And it had to be in the book.

LT: How has the book been received, and what has been most gratifying to you?

LT: How has the book been received, and what has been most gratifying to you?

CB: The book was recently selected for the Children’s Book Council 2025 Favorites Award on the Middle Grade Favorites List and the Teacher Favorites list. That my book was chosen by the middle school students meant so much to me because it’s, like I said, not an easy book to read and it speaks to how they care about this, too.

I’ve been taking it to schools and different places, and I will say that the Stigma Monster is out there. There are schools that are afraid of the content, and I have to do a lot of work with them before they are comfortable. These are adults, not the kids. And once they see it land and that it’s safe in the way it’s explained, they are converted.

My dream is to have the book be in schools, in health classes, in the places where we could point to the resources in the community and say, “you know, this book is here and here’s who you would go to for help.” I love it in the library and obviously I love it if people are bringing it into their homes, but it depends on where you live and what your resources are and what is available to you. So that’s something I’m focused on.

LT: What advice do you have for young people interested in art and cartoon art?

CB: I would say, don’t be a perfectionist, don’t wait to be really good. Just start doing whatever version of things you can do now. I know from being an older person that you are going to keep continuously improving over time, and you will build over those ideas, and maybe they will become more complex or surprising in ways you can’t imagine 5 years from now, 10 years from now, so just keep it going. Don’t stop. Even if it’s just your messy sketchbook or your doodles or your little notes, and even if you never show anybody, just don’t stop yourself from doing it. Keep it like a friend that you keep through your life.

LT: What’s next for you?

I have recently been asked by Virginia Tech and other universities to teach how to make comics that explain science. I have this weird skill now of breaking down information when it’s too complicated by asking “how can you say that a bit simpler and what images can we use to break down the text so it’s not so heavy.”

These opportunities keep coming to me, and so I guess I’m going to keep doing this. I could always be writing about drawing and creativity because that’s my passion and this emerges out of all these interactions. I’ve been keeping notes, thinking about doodling and ideas, and complexity, and how it builds.

Also, I really want to make a comic book for young people about caterpillars! Years ago, I made a little caterpillar mini-comic called “Munch”; 200 copies, not a lot, and they went out into the world. Just recently I got an email from someone in Texas who said “my four-year-old loves your caterpillar comic. Is there another one that we can read?” I don’t know where she got it but it gave me the idea that I do want to go back to caterpillars. So I might give myself a break since this book was so heavy.

LT: You offer workshops to both young people and to clinicians in “mindful doodling”: what is that?

CB: This did come out of Lexington, too, in a way. Halfway through my teaching time here, I was really stressed and I started going to therapy myself to understand myself and some of the factors that were making life difficult for me. An amazing therapist recommended meditation for me, as I had a lot of anxiety. And so I started taking a meditation class and one of the leaders, who is not an artist, had us drawing circles as part of the class. Very conscious, closed circles. I said “This is silly, I’m an art teacher. You can’t teach me anything” but it really did shift my mind about what drawing could be. Drawing as an act of calming your mind or exciting your mind or focusing your mind. It’s just a way that your hand can kind of lead your mind.

I brought it to my classroom and I found it would calm my class before I needed to explain something or bring in new material. I thought this was really cool and I just always do it. I also had graduating seniors this time of year who are so done with school and are just checked out. So as I encouraged them to at least try it, I started collecting any scientific research I could about the mental benefits of drawing. Even if you draw and you just make a big mess or spill coffee on it and you say “Oh no, what a waste of time!,” it’s never a waste of time because of all those beautiful benefits.

I used this instruction with my colleagues at LHS and then during the pandemic, offering to do zoom workshops for friends, family, and others. When the book came out these became my way of destigmatizing the topic because I’ll say “we’ll draw together, that’s not scary” and then help educators get into the content and see if it’s right for their school. It’s my way of making friends, the same thing I probably did when I was in elementary school: “Watch me draw! I made you a picture!” I’m still using that energy but at a larger scale.

LT: Based on your research and work, what advice do you have for parents, teachers, and others who want to support teen mental health?

CB: I think just being available is so important. Last night, I taught a comics class in Chelmsford and the best part for kids was me listening to their ideas and having them read their comic to me. It wasn’t how I broke it down or what I inspired in them or the intro. It was the part where I asked, “who is your character? what happens in your story?”

The point in my book is that all of us have a responsibility to each other in terms of mental health and it’s a very special thing when a young person trusts you and decides to tell you something a little heavy or let you know something’s going on. Just like me as the art teacher, I’m sure there are coaches, or science teachers, or custodians, or the lunch ladies, or, of course, parents – all of us – all of a sudden might be in the position where you’re the one someone’s telling something heavy to and you are concerned about them. We can be there for each other and it doesn’t mean we know the answers. I think that de-stigmatization helps us feel less frightened to admit when things aren’t good inside.

Like I said, you don’t have to do anything alone. You bring the person to someone that can help but you stay with them. You listen to them. You let them know that they’re not alone and this is normal and we’re going to work on this together.

RESOURCES:

For More Information about Cara Bean, visit https://www.carabeancomics.com/

For Lexington-based and other mental health resources, visit https://www.lexingtonma.gov/1712/Mental-Health-Resource

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline is a national hotline offering one-on-one support for mental health, suicide, and substance use-related problems for anyone 24/7.

No matter where you are in the United States, you can call or text the number 988 or chat online at 988lifeline.org and connect with a skilled, compassionate crisis counselor.