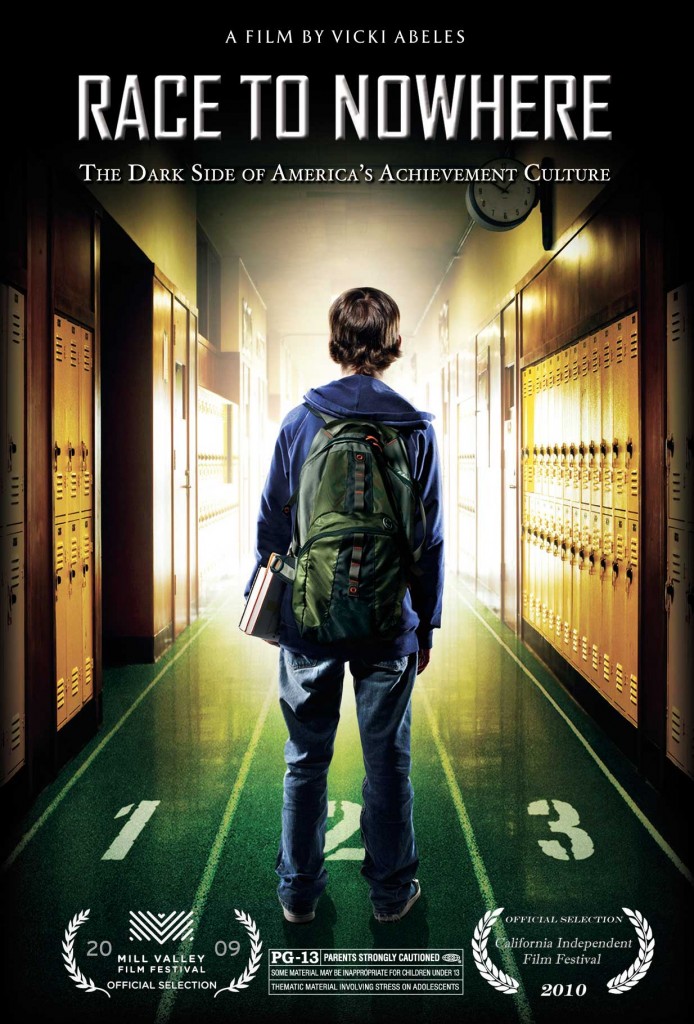

RACE TO NOWHERE-Redefining Success in a High Stress Culture

[R]ace to Nowhere is coming to Lexington. The acclaimed film about America’s “achievement culture” and the burden of stress that accompanies it, will surely open to sell-out crowds in Lexington, as it has all over the country. Make sure you do not miss this film.

this film.

I am very grateful to the Lexington Montessori School for allowing me to attend their screening of the film which was sold out the night I attended. I visited their impressive campus for the first time and was joined by parents from many different communities eager to understand the issue of stress in the schools and what they can do about it.

The film opens with a sea of students walking up and down the stairs of a school in a zombie-like state. Voiceovers say things like, “I can’t remember the last time I went outside,” or “Mom checked me into a stress center.” And saddest of all: “Nobody knows me.”

Parents in the small audience of 50 or 60 were riveted to the screen as kids gave voice to their anxieties and struggles. Most stressed about grades and homework and time, “so little time” to finish all of their resume-building activities and then just be a kid.

Kids are taking it all in. Increased global competition. Stressed-out and money-strapped parents. War. Another war. Climate emergencies. Tsunami. Floods. Fires. Nuclear melt-downs. College competition. For today’s students, it must feel relentless.

At school, they swim in a sea of competition. Competition with other kids. Competition for spots on sports teams, for leads in plays, solos in band, and coveted slots at a few elite colleges. The list goes on and on before you ever get to high-stakes testing.

IS THIS EDUCATION?

Issues arising from “teaching to the test” are plaguing school districts for both teachers and students. Attaching such high value to testing can distort the entire intent of education, turning teachers into sergeants, drilling their recruits so that they will perform well and earn accolades (and funding) for their schools. Students worry about being promoted to the next grade, and schools worry about accreditation or rankings. All of this preoccupation with tests can leave deep learning and deep thinking in the dust. In the film, teachers are demoralized, and the most passionate teacher drops out. They feel reduced to test-trainers. Their passion and joy are hijacked; they burn out.

Experts like Denise Pope, a veteran teacher, curriculum expert, and lecturer at the Stanford University School of Education are featured in the film. Pope who wrote, Doing School talks about the schools and parents sending the wrong message to students. Learning is being sacrificed for memorizing, and cheating is rampant. The goal is to cross the finish line and forget about how you got there almost instantly. And forget they do. One boy says he crams for tests and promptly “forgets everything he learned.” The fact that skills like critical thinking and problem-solving—the muscle memory of learning—are being sacrificed to a curriculum that is “a mile wide and an inch deep” is troubling. The results are beginning to show up on college campuses. The film asserts that 50 percent of Cal State and U Cal students must be remediated in freshman year.

Then there is self-esteem. Students become jaded and stressed having their existence measured by score-after-score as though they have no value beyond numerical outcomes. They quickly learn to “do school” as Pope calls it. The students who do not engage in this “race” often drop out intellectually or emotionally.

The film sets out with a big subject and in truth, it could be broken up into many films with the list of issues that it raises—ignoring middle students, the fervor over Advanced Placement classes, unprepared students who have always had “training wheels,” isolation, the consumption culture, excessive homework and more. Perhaps the most provocative question is raised by Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg, a noted expert in the area of resilience, who fears that the current system of education is stifling creativity. “Without creativity, we will have no leadership and no innovation,” he says.

RACE TO NOWHERE

In this documentary, producer Vicki Abeles, a 48-year-old lawyer, introduces us to her own children, now ages 16, 14, and 11. She details her struggles to succeed and admits that she “wanted to give them [her children] the opportunities that I didn’t have growing up.” When her kids start getting sick, not wanting to go to school, and generally acting stressed, she wants to understand why. Then, a 14-year-old student in her town commits suicide because she fails a math exam. Abeles dedicates the film to her memory.

Sometimes the film seems to swim in the soup of despair—full of anecdotal evidence from teachers and students who confront Abeles’ camera—and a little short on data-driven information. But you can understand that the voices of the teachers and kids are far more compelling than pie charts and survey results. In the end, the film succeeds because Lexington parents in attendance nod away in agreement throughout, and stay around to discuss its implications. That’s what it’s meant to do.

Many viewers may also think; This is getting old. Haven’t we been talking about student stress forever? The fact is, in Lexington, we have been talking about stress for a very long time. According to Jennifer Wolfrum, the head of school health education for the Lexington School System, this is a topic that cycles around with regularity in Lexington.

“Hopefully this film will promote conversation,” she says. “The issue of stress is not going away. It’s going to be an ongoing issue, so, it’s a matter of keeping it on the radar screen. That is my hope when we do these types of things.” While it may seem to each new group of parent activists, that the issue is new, it has actually been concerning Lexington parents for some time. Wolfrum tells me that in the mid-90s they were offering relaxation and hypnotherapy to combat stress. In the late 90s there was an academic stress committee. “I see it sort of comes and goes in waves,” she says. “They’ll be a period of time when parents or students or both will [be concerned] about it, and we do surveys and we come up with ideas and things to do to address it. And then, the energy behind it—all of the people doing these extra things—sort of dies down until it comes back again.”

LEXINGTON INITIATIVES

Right now in Lexington, the Collaborative to Reduce Student Stress (CRSS), which began as a small group at Temple Isaiah and has grown to about 50 or 60 members from different faith communities, has taken up the cause. They are doing great work with the schools and other organizations around this issue. B.J. Rudman is the spokesman for the group. “About three years ago,” he explains, “a group of mostly parents and grandparents decided to get together to see what we could do to help. There are many groups in Lexington that deal with youth, the schools, the town, and the PTAs; we want to collaborate with these groups with a particular focus on reducing stress.”

Rudman sees the screening of Race to Nowhere as a perfect example of how the group can be helpful. “The idea actually came from the SHAC (School Health Awareness Committee) group at the high school. Many people have raved about the movie,” Rudman says. “The CRSS decided to step up and offer to plan the event.” Their volunteers have organized the screening and will staff the event. Following the screening, on May 5th at 7 PM there will be a moderated community discussion there will be a community discussion at Temple Emunah. CRSS has also helped SHAC create their new website http://lhs.lexingtonma.org/Stress.

My perspective is, a key to change is a change in community attitudes. People need to be educated and this is a very powerful way to do it,” Rudman says. “We recognize that some stress is good, but too much stress is not healthy and ironically, too much stress actually inhibits academic performance.”

The scientific literature on stress and performance has been well documented in recent years and more recently it’s being updated to include research into the effects of technology on the developing brain. It may not be that academic stress and the focus on high-stakes testing is the single driver of this epidemic of stress that we are seeing; technology may also be playing a major part in the problem.

TECHNOLOGY, STRESS, AND THE TEEN BRAIN

Dr. Sion Harris, a Lexington resident, and member of SHAC, is a researcher at Children’s Hospital specializing in adolescent substance abuse and prevention strategies. She also has two children in the Lexington public schools.

“What is a 24/7 plugged-in world doing to brain development and our ability to maintain attention?” she asks. “Especially in adolescents whose brains are not fully developed. It does require effort and high-order brain processing to be able to focus and tune out distractions,” she adds. In fact, teens are being bombarded by information all of the time—especially now that their phones are essentially pocket computers, keeping them linked to the internet. “We know that teens don’t have the prefrontal cortex development to be able to inhibit these behaviors,” Harris says. In other words, they can’t resist the urge to text or to go on Facebook if it’s available—even if they are supposed to be doing something else like homework. Even adults have a difficult time putting down the Blackberry,” Harris laughs. “You can really see why the stress is ratcheting up.” According to Harris kids are staying up all night texting and losing valuable sleep and brain processing time. “There are definitely casualties to being over-stimulated and over-connected, and I do think that is one of the reasons that kids are more stressed today.”

But it’s not the only reason. As Race to Nowhere illustrates, high school students are clearly very concerned about being “successful” in life. What that has come to mean in our society is following a certain path of achievement—a high achieving high school student with a great resume gets into a top college (preferably an Ivy League school) which will guarantee the American Dream. This scenario is becoming more unrealistic as colleges become more selective and expensive. “We need to redefine what it means to be successful in this culture,” Harris says.

Dr. Blaise Aguirre is an instructor at Harvard Medical School and the medical director at 3East at McLean Hospital which specializes in treating teens and young adults. “Academic stress is real,” he says, “and kids do feel the real and competitive nature of their school lives. However, academic stress is not the only stress that causes anxiety among students.” He cites a study in which 4,300 students were exposed to a list of common negative life events. Students were asked to check those they considered “bad” that they had experienced in the previous six-month period. The results were compiled into a list of the most frequently reported events. Academic stress and school didn’t even appear in the top eight. “Most kids admitted to hospital because of stress-related depression,” Aguirre explains, “are [there] because of relational issues and not academic stress.” But, according to Dr. Aguirre, there is also no question that any form of stress “is neurobiologically tied to depression.” In individuals with a genetic predisposition, it is a stronger link.

Dr. Harris says that her work has shown her how important it is for children to develop social-emotional competencies when they are young. If we are going to address this culturally, we need to engage the parents of younger children. “Over the course of my work, she says, “I see how much social and emotional competencies are important in kids.”

Social competency and resilience are protective agents when it comes to the adolescent brain. The teen brain is impulsive and prone to risk-taking. Kids without coping skills often become depressed or engage in behavior that can be dangerous to their own safety. “Resilience can be innate for many people,” adds Dr. Aguirre, “but for those who do not have it, it can be taught.” In fact, Dr. Aguirre uses mindfulness in his practice with young people.