The Myth of a Post Racial America

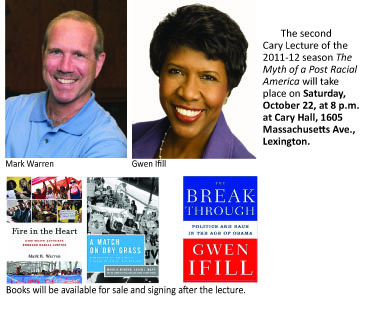

H ere in Lexington we are lucky to have the opportunity to live among great thinkers and to have them invite their friends to town! That’s why the Cary Lecture Series will be hosting a Gwen Ifill and Mark Warren on the same stage this week. It turns out that they were students together in Springfield, Massachusetts along with Bob Halperin who is a Cary Lecture committee member and director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence. It’s a great opportunity for this trio to reunite and for Lexingtonians to hear Warren and Ifill speak on The Myth of a Post-Racial America.

Gwen Ifill is the best-selling author of The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama. She is moderator and managing editor of Washington Week and senior correspondent for The PBS NewsHour.

Gwen Ifill is the best-selling author of The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama. She is moderator and managing editor of Washington Week and senior correspondent for The PBS NewsHour.

Mark Warren is a sociologist at Harvard and has spent his career studying and writing about social justice and the revitalization of American democratic and community life. He is the author of Fire in the Heart: How White Activists Embrace Racial Justice and Dry Bones Rattling: Community Building to Revitalize American Democracy.

I talked to Professor Warren right after the abysmal poverty rates were released showing that black Americans have been very hard hit by this recession with black poverty at almost three times that of white families and almost fifty percent of all black children growing up in poverty.

“That’s an unbelievable figure,” he states as we talk by phone. “All Americans are being hard-hit by what’s going on with the economy, but the problem of black poverty and black unemployment points to persistent racial inequality,” he says.

What interests him and what he has spent a lot of time studying is the intersection between whites and blacks and the ways in which they can work together across the color line and social class on issues of social justice.

“The problem of black poverty or black unemployment is not just a problem for black America,” he says. “It’s a problem for our whole society. We are not going to be a strong society when 50 percent of black children grow up in poverty. There are lots of different ways that this is important for white people. Too often I think white people approach this from a “helping” perspective: helping black people. But it’s in our own self-interest to have a well-educated and productive workforce in this country.”

In his work, Warren has interviewed many white people from different walks of life who have become involved in issues around racial inequality. Most of them had a seminal experience that shaped their thoughts and feelings about racial injustice. From dramatic stories right out of the sixties to the more subtle observations of young people today, his book illustrates the ways in which white people can be shaken out of complacency and into action by events or people.

Relationships are key. “Understanding and caring come, at least in part through relationships,” he states. “That’s why I think the community level is so important for this work. We need more places [for people to interact], so this is a tough message. Our segregation reinforces our differences. Personal relationships can be powerful; this is a profound way that people come to understand the world and the experiences of people of color.”

I ask Warren how people can take steps in their own lives to become involved. “There are types of ways that we can try to connect to each other’s lives. Faith communities are often interested in bringing people together across different faith traditions and communities.”

Does he think that there is an “empathy deficit” in the country right now. He responds: “When times are tough as they are right now,” Warren says, “people tend to hunker down and take care of their own; stop worrying about other people because they feel under threat. But we can also understand that we’re all in this together and we need to find resources together. This is an economic issue, but it’s also a moral issue. What kind of society do we want to live in; all of us together, not just black people? It’s a long-term issue. Doing the kind of research I do, I don’t have an answer for this, and in a way that’s not surprising since it’s been going on for three hundred years!” he says.

Does he see fatigue among middle-class whites who may live among middle-class black families and feel that everything is just fine with black America; especially since we have a black President?

“Well, we have made progress,” he says and that’s important to acknowledge. We should recognize this and ask ourselves what profound things still remain in our society. We did change in the sixties and seventies. We had a social movement that galvanized the conscience of people all across the country; not just African Americans. It was during that era that there was a lot of progress in education and affirmative action and many of the successful black people are younger beneficiaries of those struggles, including Obama. But there’s enough information out there about how difficult things are right now, so it’s a little self-serving to think that it’s all behind us.”

How might a person attending his lecture get involved; what would he recommend? “Try to work within a group or institution where you’re already involved: your church, your school, or another organization that you care about. Working within your own circle of influence and with your own relationships is important. Find other like-minded people.”

In his work, he discovered that white people can’t do this alone. “You really have to form groups not to isolate yourselves, but to have the support and encouragement of a community and to hopefully find ways to reach across racial lines so we can work on some of the issues we are trying to get at in our larger society. What does a community look like where people know how to work together and respect each other? That’s what we want for our larger society. That may mean taking a step outside your comfort zone,” he says.

I comment that stepping into a multi-racial group can be stressful for many who are simply afraid that they will say the wrong thing or inadvertently offend someone. “This is a hard one,” Warren says. “We all have been raised in a racist society and often segregated societies, and it’s not surprising at all that we may have beliefs that reflect our backgrounds. We don’t want to defend that, but on the other hand we don’t want to be crippled by it. A woman I interviewed had a great way of putting it; she said “A lot of white people are afraid of making the same mistake once!” Despite difficulties, Warren says “Most of the white people I’ve interviewed for my book really want these different types of relationships “they value these experiences in their lives.”

On an upbeat note, Warren does a lot of work with college students. “Students today are more concerned about their economic future than they were a few years ago,” he explains. “So many students are very concerned about issues of injustice around race and poverty.” Warren serves on the board of the Phillips Brooks House Association at Harvard, a student-run organization for social justice. “We have eighteen hundred members,” he says proudly.

Read more about Mark Warrens research and books at www.mark-warren.com.