Turkey – The Truly American Bird

While Virginia claims an earlier similar event, the commonly recognized first American “Thanksgiving” took place in 1621 at Plimoth Plantation when Puritan Governor Bradford and about 53 Pilgrims got together with 90 Wampanoag Indians, including the tribe’s legendary king Massasoit (for whom Massachusetts is named).< br >

The feast sealed an alliance between the two groups and celebrated the colonists’ first harvest in the New World. Venison rather than turkey was the main course. Warriors from the tribe brought five fresh killed deer to the feast. Rather than a few hours, this harvest bash lasted for three days. Although no specific date has been established, it was probably held sometime in October. Surprisingly, despite abundant wild turkeys available to hunt there is a controversy as to whether they were on the initial bill o’ fare. Apparently the partying Pilgrims preferred duck and goose to the wily gobbler, a bird that was coveted more for its feathers than its taste by the Native Americans, who considered it “starvation food.”

Our domestic turkey is hardly the same as the wild turkey that was indigenous to New England when the Pilgrims arrived. As the European invasion spread westward, it hunted the native turkey into near extinction. According to the Department of Energy and Environmental Affairs, the wild populations of turkeys in Massachusetts had been completely eliminated by 1851. The wild turkey might have gone the way of the carrier pigeon if it had not been for a dedicated group of turkey enthusiasts who in the last century began to reintroduce the species to areas where it had once flourished.

The turkey is a bird to be admired on many levels. There is even a story that Benjamin Franklin argued that the turkey should be our National Symbol rather than the Bald Eagle. He talks about it in a letter he sent to his daughter Sally from France on January 26, 1784: “For my own part I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen the Representative of our Country. He is a Bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead Tree near the River, where, too lazy to fish for himself he watches the Labour of the Fishing Hawk; and when that diligent Bird has at length taken a Fish, and is bearing it to his Nest for the Support of his Mate and young Ones, the Bald Eagle pursues him and takes it from him.

With all this injustice, he is never in good case but like those among men who live by sharping & robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank coward: The little King Bird not bigger than a Sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district. … For the Truth the Turkey is in Comparison a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America…He is besides, though a little vain & silly, a Bird of Courage, and would not hesitate to attack a Grenadier of the British Guards who should presume to invade his Farm Yard with a red Coat on.”

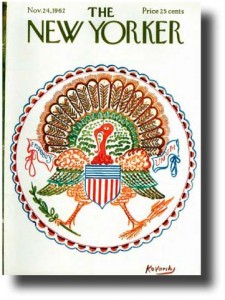

The legend of Franklin and the turkey was further cemented in November 1962 when the New Yorker magazine published a cover by artist Anatole Kovarsky (left) taking Franklin’s idea a step further and depicting the Great Seal of the United States with a turkey pictured in the center.

The legend of Franklin and the turkey was further cemented in November 1962 when the New Yorker magazine published a cover by artist Anatole Kovarsky (left) taking Franklin’s idea a step further and depicting the Great Seal of the United States with a turkey pictured in the center.

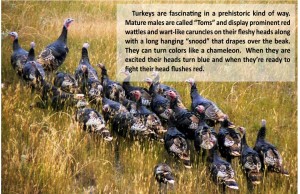

Turkeys are fascinating in a prehistoric kind of way. Mature males are called “Toms” and display prominent red wattles and wart-like caruncles on their fleshy heads along with a long hanging “snood” that drapes over the beak. They can turn colors like a chameleon. When they are excited their heads turn blue and when they’re ready to fight their head flushes red. In addition to their prominent fan-shaped iridescent display feathers, adult males have long “beard” feathers jutting out from their chests. Juvenile males are called “Jakes” and although similar to the adults can be differentiated by their shorter beard and a tail fan that has longer feathers in the middle. The adult fan is the same length throughout. Wild turkeys can gather in huge “rafters” of up to 150 birds or strut around the woods by themselves.

These days the suburban bird doesn’t seem too afraid of humans. I had one perched on my back wall every day for about a week a few years back and I watched a gang of eight running across the lower end of Concord Ave. just the other day. Wild turkeys are here to stay and as human interaction increases we need to know a little bit about how to deal with them. Both MassWildlife and the Department of Energy and Environmental Affairs recommend not feeding wild turkeys. Not only does it disrupt the natural order, you just might be opening Pandora’s Box. One of our mail carriers told me this cautionary tale. Thinking he was doing the right thing, he tossed a few crumbs out to a turkey that happened by his yard one day. Big mistake, “The next day there were four turkeys in the yard and the day after that there were twenty.” One turkey is cute. Twenty turkeys can be a little scary.

If you are ready to go and catch your own turkey Pilgrim-style you won’t have to rely on a handy blunderbuss. Turkey hunting has become a highly specialized affair. Considering that the wild turkey has almost reached nuisance status, it’s hard to imagine that wild turkeys were only reintroduced to Massachusetts 40 years ago. With the cooperation of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, MassWildlife trapped 37 turkeys in southwestern New York and released them in Beartown State Forest in the Berkshires in 1973. In 1978 they began to relocate birds from the initial group to other locations across the state. From there the turkey population literally exploded. Today they inhabit every mainland city and town in the Commonwealth. Currently the state’s turkey population is estimated at well over 30,000 birds. In Massachusetts the recovery has been so complete that limited hunting is allowed for this prized game-bird in the spring and fall.

Turkey Shoot

The wild turkey is considered one of the toughest birds to hunt and is highly respected by sportsmen. I got to talk to Bob, one of the hunting experts at Bass Pro Shops, the local mecca for sports hunters. I wanted to know what it would take to outfit myself for a turkey hunt. To be honest, I didn’t think turkey hunting would be such a challenge.

I’ve often seen the crazy birds brazenly stopping traffic on some of the main drags around town. I figured all I’d need was a loaf of bread and a hammer to bag my quota. Bob assured me it would be a little more complicated than that. “Their eyesight is phenomenal. There’s no rhyme or reason as to what turkeys do. The trick is just don’t move. Call them, and have them come in on a decoy. Hope they come in on your line of sight because if you have to swing your gun, you’re not going to get them.” Because turkeys roost in the trees at night Bob gave me an excellent tip: “Go out after dark and blow a crow call. The turkeys will respond to it because they don’t like crows.” Once you’ve located the general area where the turkeys are roosting you can return around dawn the next morning when they are leaving the trees to begin their activity.

I’ve often seen the crazy birds brazenly stopping traffic on some of the main drags around town. I figured all I’d need was a loaf of bread and a hammer to bag my quota. Bob assured me it would be a little more complicated than that. “Their eyesight is phenomenal. There’s no rhyme or reason as to what turkeys do. The trick is just don’t move. Call them, and have them come in on a decoy. Hope they come in on your line of sight because if you have to swing your gun, you’re not going to get them.” Because turkeys roost in the trees at night Bob gave me an excellent tip: “Go out after dark and blow a crow call. The turkeys will respond to it because they don’t like crows.” Once you’ve located the general area where the turkeys are roosting you can return around dawn the next morning when they are leaving the trees to begin their activity.

So what will it cost you for a turkey hunt? Once you pay for your license and ammo you’ll need a complete camouflage outfit, along with a turkey hunting vest with a brand name like “Thunder Chicken” or “Ol’ Tom,” one of the 202 choices for a turkey caller, an optional crow call, a couple of turkey decoys, and of course a super-deluxe fully camouflaged 12 gauge Remington short barrel turkey shotgun. The total cost to get you started: $2000 – $2500. In comparison, that buys about 500lbs of store-turkey @$5.00/lb.

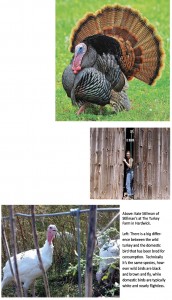

There is a big difference between the wild turkey and the domestic bird that has been bred for consumption. Technically it’s the same species, however wild birds are black and brown and fly, while domestic birds are typically white and nearly flightless. Wild birds are mean and lean. Domestic birds are bred to be BIG and especially to have more breast meat. And while the wild bird is cantankerous and combative, the domestic version has been engineered to be less aggressive.

Turkey Farming

If you don’t have the patience for hunting and are going the more traditional route of snaring your turkey at a store, the modern chef has more choice than ever before. During the second half of the 20th century turkey farming was aggressively consolidated. Family farms began to disappear and large farm conglomerates raising over 50,000 birds at a time became the norm. Driven by profit, these huge businesses often employed inhumane practices and questionable additions of growth hormones to maximize their returns. Beginning in the 1950’s the industry also heavily marketed the modern image of Thanksgiving with the perfectly roasted turkey at its center.

Current Practices

More recently, public awareness and demand for a more natural and humanely bred bird has challenged that model with smaller high-quality operations and boutique farms that specialize in free-range and “all natural, cruelty free” birds. Rather than preparing your banquet with a frozen turkey, places like Wilson Farm and Stillman’s at the Lexington Farmer’s Market offer tasty alternatives.

Mark Silvano is the turkey buyer at Wilson Farm. They supply locals with about 2000 all natural, no antibiotic, humanely raised and processed birds every Thanksgiving. He is proud of their product: “It’s certainly not a turkey you can get anywhere else. It comes in a clear bag so you see what you’re getting.”

For years Wilson’s has been getting its “fresh not frozen” turkeys exclusively from Jaindl’s Family Farm of Orefield, PA. The farm emphasizes their turkeys are “raised on corn, wheat and soybeans in open large barns, not cages. No growth hormones, nor animal by-products or fish meal is in the feed.” Wilson’s has to place turkey orders 6 months in advance in order to meet holiday demand. Customers can reserve a bird starting in November either by phone, at the farm, or online. Mark never worries about selling out. He smiles, “If there is anything left over, there will be a big sale on turkey pot pies.”

If you prefer your turkeys raised and processed locally, Stillman’s at The Turkey Farm in Hardwick is a terrific choice. A regular at the Lexington Farmers Market, Kate Stillman has been raising turkeys for the last eight years. When she first bought the farm, turkeys were not in her game plan. “Turkeys are not as entertaining as pigs or sheep.” But the first time Kate pulled into the only gas station in her small town, “the attendant said, ‘Oh, you bought the old turkey farm.’” She laughs, “I figured if everybody knew it as ‘the turkey farm’ I’d better start raising some turkeys.” She later met one of the members of the original family who had operated the farm since 1830. At that time the farm was raising more than 5000 free-range birds.

Currently Kate manages around 500 birds along with the rest of her farm animals. Remarkably, a turkey can grow from a newborn poult weighing a few ounces to a full-grown bird topping the scales at 30lbs within 6 months. Kate starts taking holiday orders beginning in August and is enthusiastic about her product. “How we raise them. That’s what makes them taste so good. That’s the biggest advantage. Even if you go to a high-end grocer, it’s not the same thing as buying a local free-range bird. The taste difference is profound.”

Personally, I’m amazed at the speed with which the wild turkey has been able to reestablish itself in our local woodlands. Today they are almost as common as crows. I tip my hat to the tough and cocky symbol of our annual holiday feast.

Now if they could only learn to cross the road in the crosswalks.