Inheriting the Trade – Reflecting on the Slave Trade

March 2011

Traces of the Trade was an official selection of the 2008 Sundance Film Festival.

Nominated for an Emmy for “OUTSTANDING INDIVIDUAL ACHIEVEMENT IN A CRAFT RESEARCH”.

Winner of the Henry Hampton Award for Excellence in Film & Digital Media from the Council on Foundations and Grantmakers in Film & Electronic Media.

Hidden History

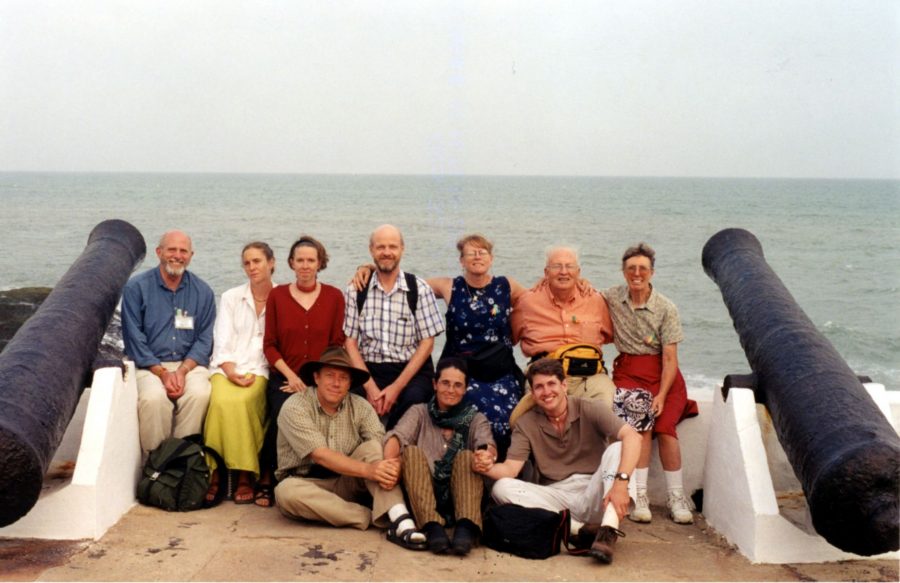

Browne learned of this history from her grandmother on the DeWolf side. The DeWolf family of Bristol, Rhode Island is respected and well-known. Katrina Browne was shocked to discover that her Rhode Island forebears had been the largest slave-trading dynasty in American history. For two hundred years, the DeWolfs were distinguished public servants, respected merchants and prominent Episcopal clerics, yet their privilege was founded on a sordid secret. This hidden history was not discussed within her family, but Katrina realized through her extensive research that three generations of DeWolf men were the biggest slave traders in U.S. history. Once Browne started down this path, she contacted her cousin James DeWolf Perry. They convinced seven fellow descendants to journey with her from Rhode Island to Ghana to Cuba. Browne and Perry began digging for information: journals, ship logs, old ledgers, letters, and other family memorabilia told a troubling tale. How could this upstanding Episcopal family of public servants, clergymen, merchants, and solid citizens be human traffickers?

In 2009 they founded The Tracing Center to continue the work they started with their Emmy-nominated PBS documentary.

Recently, I spoke with James DeWolf Perry by phone.

“Katrina had approached me early on and asked if I had heard about some history of slave trading in the family,” he explained. “She wanted to make a documentary film, and I thought that was a really wonderful idea and I was helping her to raise money and do some research. So, by the time she discovered that our family had been the leading slave traders in the east, I was already deeply involved in the project.” DeWolf has spent practically a decade since the making of the film devoting himself to educating and speaking to groups about the slave trade and its impact on our country. Perry received an Emmy Award nomination for his role as a historical consultant for the film.

The Profit Motive

“Generally, economic historians say there have been times in history when slavery was profitable and times when it was not. In every era that it was profitable, societies have done it. It’s hard to find great societies that didn’t condone slavery at one time or another. What happened with slavery is driven by economic self-interest, and it is something that human beings are perfectly capable of being a part of,” DeWolf says.

Economic opportunity also drove the supplier side of the slave transaction. “Every single person who was sold as a slave was enslaved by Africans and traded to white traders on the coast,” DeWolf says. “These societies were never trading their own people; they were trading people they thought of as others.” He explains that slaves were often captured deep into Africa and walked hundreds of miles to the coast where they were first sold to Europeans and then later, to Americans. “Groups in African society jumped at the chance to make huge profits,” DeWolf says.

Not Just a “Southern” Problem

“Getting people to understand their own connection to this history is always a challenge,” DeWolf says. “While it’s true that most families did not have a direct family link to the slave trade, everyone was indirectly involved.” In fact, many common people bought shares in slaving trips as investors, just as you would buy shares in the stock market today. They shared financially in the successful sale of Africans. Outfitting these slave trading missions kept many people employed, from bankers to provisioners. The philanthropy bestowed upon various cities and towns by wealthy merchants like the DeWolf family— is still evident today.

DeWolf makes the point that New Englanders have rewritten their history to omit their complicity in the slave trade. But in fact, it was the businessman in New England states, “especially Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut,” who created the Triangle Trade and supplied the South with slaves.

Before the American Revolution, the primary crops in the agrarian South were tobacco, indigo, and rice. Slaves and indentured servants were used to grow and harvest these labor-intensive crops that were ultimately exported. This expanded the economy of the colonies. The financial success of the colonies was also dependent upon the sugar that was procured on slave trading missions and made into rum stateside.

Slavery peaked in the late 1700s and was declining until the invention of Eli Whitney’s cotton engine (gin) in 1793. This machine, which mechanized the removal of sticky seeds from short-staple cotton, revolutionized the agricultural model of the South. The South’s soil and climate were perfect for growing cotton, and suddenly this labor-intensive crop could be hugely profitable. Farms began springing up across the South to meet the demands of English textile mills. Slavery, once again, became a huge money-maker as the demand for labor rose. Huge shipments of bales of cotton regularly left American ports bound for mills in England.

Eventually, Americans began getting in on the action and started to open cotton mills of their own (many of them the slave traders themselves). “The whole reason we have the mills in Massachusetts was because of the cotton picked by slaves. Wherever we had rivers, we saw cotton mills—in Concord, Newton, Watertown, and Lowell. And of course, at that time, everyone understood that connection to slavery,” DeWolf explains.

“When we started to rewrite how we thought about our history here in the North, we downplayed slavery. We didn’t hide it completely, but we pretended it was a brief thing, and we started to think of ourselves as having a powerful abolition tradition at the same time. We washed away the many other economic connections to it,” he says.

DeWolf also talks about the widely held notion that the North was a righteous hotbed of abolitionists. “It is true that New England, along with other places like Philadelphia, spearheaded the abolitionist movement,” he says. But he adds, “The white working class in Massachusetts was very worried that freed slaves would be competition for wages after the Civil War.”

Collective Responsibility?

Understanding this history has put the DeWolf family unwittingly at the center of an issue that they never thought much about. What is our shared and ongoing responsibility for this shameful part of American history, and what can we do about it? This is perhaps the most important work of the film and the filmmakers.

Moving the film into the public sphere through communities, schools, public television, and religious organizations has allowed Browne and DeWolf to spread the word about the business of slave trading, its ties to the Northern states, and its impact on the country’s economic development. There is little doubt that the profits from the slave trade and the free labor it provided built an economy that was strong enough to free itself from Britain.

The film argues that slave labor is part of the very foundation of our country and that every citizen has benefitted from the proceeds of that labor, with the ironic and tragic exception of the direct descendants of the slaves themselves.

The legacy of slavery has left us with African Americans who still suffer the consequences of years of being classified as second-class citizens. While their families were torn apart, and both men and women were forced into labor and servitude, white families from all strata of society profited from the fruits of that labor.

Through the exploration of this one family, we get an interesting look at racial attitudes across white socio-economic lines and a revealing exploration of “white privilege” through the lens of their family experience. We get a glimpse into the black/white divide as it exists today” and the difficulty of connecting to events in the past.

According to DeWolf, the concept of white privilege is not readily understood by whites. “It goes to the very heart of who we are,” he says. “Whites want to believe that they have gotten where they are because of hard work and merit.”

Through explorations of family dynamics, this film exposes just how sensitive people can be on that topic. In one scene, DeWolf’s father feels compelled to explain that he would have gone to Harvard whether he was or was not a DeWolf. He asserts that his family had no money (not all DeWolf descendants shared in family wealth), and his father was a minister. He worked hard and got to Harvard on his own merits, he asserts. But, he neglects to say that his father also went to Harvard as did his father. Legacy admission in higher education is a type of white privilege that many less-privileged whites don’t even enjoy!

Another cousin argues to the camera that he was not as privileged because he attended the University of Oregon. Failing to recognize their own privilege is just one example of how people don’t connect the dots when it comes to race, according to DeWolf. It’s so emotional, DeWolf admits. “That’s the way privilege and oppression have always worked. It’s the fine gradations that allow people to look up from where they are. When people are given a little more privilege they tend to bond with the system and defend it.”

Not My Problem

James DeWolf admits that the conversations that happen around the screening of this film can be quite difficult.

“Part of it is people are coming to the material from different backgrounds and from different life experiences,” DeWolf says. “Also, people can have different philosophies, and it’s such a big topic.” Certainly, it is a loaded topic. “When people are confronted with the history, their first response is often, ‘This isn’t me!’ Because this happened so long ago and because it has been whitewashed in most history curriculums, we naturally feel distanced from it. Avoidance is part of our inheritance,” he says, “and it is very human.”

It is especially difficult for people whose families immigrated to the United States many years after slavery had ended. But, DeWolf says that these immigrants came because of the financial opportunities that were created during the industrial revolution. “Opportunities that would not have existed without cotton. And, cotton was grown and harvested through slave labor.”

Many feel that because their families came to America after the Civil War and didn’t own slaves, they weren’t complicit. This simply denies the history, according to DeWolf. It is especially difficult when they know that their own families also experienced so many hardships in pursuit of a better life in America. But, DeWolf says, “They had white skin, and because of that, it was automatically easier for them to succeed. Even if they [immigrants] had little in the way of education or money, just by virtue of being white, the moment they walked off the ship, they were walking into an upper echelon of American life. Being poor and white gave their children access to opportunities and education that black families did not have.”

Post Racial?

African Americans in our society start off at a different point. “If you’re born black in this society, you’re not likely to have access to the same opportunities,” DeWolf explains. “People who want to put this all behind us are mistakenly under the impression that the history is no longer affecting us, that in the 50s and the 60s we had a Civil Rights movement and everyone has had equal opportunities since then,” says DeWolf .

DeWolf claims that there is fatigue on both sides of the issue. “But in the case of race, we still have a great deal of prejudice in our society and a great deal of inequity. We have made progress in many ways, but it is the ways that we have not moved on from the history that needs to be addressed,” he says.

Some intellectuals and political activists in both the black and white communities feel that at this point in history, after affirmative action, desegregation, and the many social welfare programs designed to assist the black community, their lack of economic and social progress is their own fault.

This is simply not the case, DeWolf says. Lack of social mobility can be traced back to unfair practices across all areas of society, from education to employment to credit. These practices grew out of prejudice that has its roots in slavery. When you count people as less than 100 percent human, as we did to blacks in the United States, the attitudes persist.

Many of these attitudes led to practices that were hidden from view, including the notorious red-lining mortgage practices by banks, which were designed to keep blacks from moving outside of the cities and into the suburbs. The concentration of urban black populations in the cities has made them vulnerable to poor schools because property taxes finance schools. Lack of education is directly tied to a lack of social mobility. And the cycle continues.

Ever since the election of Barack Obama, people have been discussing a post-racial America. But if America were indeed post-racial, the statistics on blacks across all measures of social mobility would show less disparity with whites (and even other minority groups).

This compelling lack of real progress since the civil rights era is what inspires DeWolf to keep this conversation moving forward into communities, schools, and faith organizations. “As a family, DeWolf says, “we support a national dialogue and education process to lead the United States toward racial reconciliation.”

Learn more about the Traces of the Trade project HERE

Learn more about The Tracing Center HERE

Also Check out this book from Thomas Norman DeWolf and Jodie Geddes:

The Little Book of Racial Healing is available NOW from the Good Books imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, this new addition to the Little Books of Justice and Peacebuilding series presents the Coming to the Table Approach to racial healing in book form for the first time. PLEASE NOTE: 100% of author proceeds from this Little Book are donated to Coming to the Table to support the racial healing work described within its pages.

The Little Book of Racial Healing is available NOW from the Good Books imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, this new addition to the Little Books of Justice and Peacebuilding series presents the Coming to the Table Approach to racial healing in book form for the first time. PLEASE NOTE: 100% of author proceeds from this Little Book are donated to Coming to the Table to support the racial healing work described within its pages.

Coming to the Table (CTTT) was born in 2006 when two dozen descendants from both sides of the system of enslavement gathered together in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, in collaboration with the Center for Justice & Peacebuilding at Eastern Mennonite University. Participants envisioned a more connected and truthful world that would address the unresolved and persistent effects of the historic institution of slavery. This Little Book describes the Coming to the Table Approach to racial healing; a continuously evolving set of purposeful theories, ideas, experiments, guidelines, and intentions, all dedicated to facilitating racial healing and transformation. The CTTT Approach includes principles of Restorative Justice, Trauma Awareness, use of the Circle Process in group dialogue, and four interrelated pillars: Uncover History, Make Connections, Work Toward Healing, and Take Action. The CTTT Approach, and this Little Book, are committed to a vision of a just and truthful society that acknowledges and seeks to heal from the racial wounds of the past – from slavery and the many forms of racism it spawned.

Learn more about the Coming to the Table method HERE